The Indecisive Moment: Street Photography & AI

Of rhythms and algorithms. / Reprinted in PetaPixel and DIY Photography.

Of rhythms and algorithms.

I realized I wanted to photograph time. You can’t see time, and you can’t touch it. That’s why it’s the furthest thing from our five senses. But with photography, I can capture time.

— Miyako Ishiuchi, What Photographers Go Up Against 6: Time

I’ve spent countless hours walking streets both near and far from home with My Precious in my hand and a muscle-memory for it in my fingers that made it effectively part of me — an extension of my arm. My Precious is, of course, my camera.

Years ago I wrote about the “Zen” of street photography, by which I meant its meditative nature for me — how its practice enlivened my senses to the world around me, made me walk more slowly and observantly — excruciatingly (and often exhaustingly) mindful of the world around me. I wrote somewhere once that of every street photo I take — no matter how long ago, no matter how many 1000s of photos I’ve taken — I remember exactly where I was standing and what the scene sounded like around me. A synaesthetic frisson generated by a sea of sensory data in the depths of my physiology.

“The decisive moment” is a phrase often used to describe the essence of street photography as a practice and genre, coming from a canon work by Henri Cartier-Bresson in 1952:

Photography implies the recognition of a rhythm in the world of real things. What the eye does is to find and focus on the particular subject within the mass of reality; what the camera does is simply to register upon film the decision made by the eye[…] Photography must seize upon this moment and hold immobile the equilibrium of it. […] Photography is the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.

— Henri Cartier-Bresson, The Decisive Moment

What is this “mass of reality” and how is this decision made? Consider all the variables of environment and motion at play — the light at that exact time of day, the street corner that is turned (or not), the speed at which human bodies pass each other, the direction the eye is looking for a split second because a sudden sound was heard. The height of the standing photographer. The bend of a knee or wrist.

Bowie ponders a passerby.

Somewhere in all that mass, that chaos — something in the mind and finger of the photographer makes a wordless, instant decision to take a photo — capturing a moment in time that never existed before and never will again. What is that recognition of a rhythm? It’s a profoundly human algorithm.

I once hacked my own photography practice by taking away almost all my own agency around it. I built a tiny camera that I could pin to my clothes and programmed it to automatically take a picture every 60 seconds, then simply went about my day. Later, it felt deeply weird to see the results for the first time — as though they were taken of my life by a stranger, a portable paparazzo. It was a fascinating experiment in loss of control, discerning where my artistic eye begins and ends, and feeling intimately witnessed by something outside of myself.

Lately, I’ve been seeing increasingly-common rules in announcements for street photography competitions that say “no AI-generated images” and the like. The first time I saw this, it struck me as odd because it seemed obvious… like, of course, [by its very nature and definition] it can’t be AI-generated; it is necessarily of physical worlds and the messy people in it and time itself. AI does not exist in time or space.

Right?

Something of a meta street moment.

A fellow street photographer I’ve been following for years recently and suddenly became an exclusively generative-AI artist. My heart sank as I’d really loved his poetic, ethereal, and unusual work that had inspired me over and over again. His new style was glossy and almost-wholly disconnected from his earlier aesthetic and point-of-view, seemingly (to my eye, anyway) entirely text-prompt-based and not using any of his own original work as material. It was still beautiful and imaginative work, but it told me nothing about what he’d seen or lived. There was still much to appreciate about it artistically and technically, but I realized that what I’d loved was the stories he told about the world — and how he, specifically and as a fragile and imperfect being, moved in it.

While I can be a romantic about more traditional practices — and was initially tempted to immediately throw a rope between “real” and evolving tech in street photography — I’ve come to think that any difference is ultimately semantic vis-à-vis how we categorize art. I think it’s a lot more interesting to find intersections of human and machine ,and all the literal and figurative shades of gray between them. What is a camera anyway but a mechanized eye invented by puny mortals to try to capture time?

During the early years (!) of the pandemic, I grieved the freedom of being able to travel freely through my own neighborhood and favorite places in the world. I began to digitally composite together photographs I’d taken — over different years and places —to create worlds both familiar and new, like Mt. Rainier of my Washington home emerging over Tokyo. It felt like time travel and it felt true to my soul. I could feel where I was. It felt like memories and testimony of places I’d walked… that don’t actually exist. Like fusion and bottled magic. And it was all real… just remixed, reimagined.

Simple example of a composite. I combined a Tokyo street scene with textures of a Pacific Northwest forest.

In my day job as a product designer in tech, I started working in AI in 2017 and am as ever in awe of it, in all the senses of that word. I mostly worked in the area of natural-language processing and virtual assistants like Alexa or Siri, and have some exposure to its use in computer vision (CV), consumer robotics, and smart wearables. I both enjoy and am agape to imagine how we might deploy such tools with regard to photographic art and craft. I think of the tiny wearable camera I made and what if I had glasses like that. And I think about how much I’d love to train a custom AI model (for my use only!) with the tens of thousands of photos I’ve taken over the years to generate wild new versions of my own work free from temporal and geographical bounds, soaring creatively in a world of my own curation. All that visual data! My eyes gleam with the possibilities.

I used to spend hours editing and cropping and tinkering with my photos, something I no longer do because now I just program My Precious’ settings to take photos to my exact artistic aesthetic: the exact lighting and color effects, the exact level of grain, my preferred aspect ratio, and so on. I now just compose and take the shot and its done right out of the camera. It’s not a huge leap to imagine that I could train it over time to detect what scenes I find most compelling, what angles I use, how I compose and frame, and ultimately how I share my life and how I see the world with others.

But, what would be the fun in that?

Reprinted in PetaPixel and DIY Photography.

1-Minute Creative: Upcycle Your Low-Res Photos? AI Says Yes.

How to make your low-resolution photos effectively high-res if you wanna print or publish them.

This is the first entry of 1-Minute Reads for Creatives.

I’m a photographer. You’re a photographer. We’re all photographers now.

My first camera in the 1970s, as a tiny child, was an ancient family Kodak Land Camera, i.e. a black-and-white instant camera that looked like an accordion from the 19th century to my eyes. These days I’m a street photographer, among other things. I publish and exhibit and sell photography. I have many beautiful photos taken on older digital media. As they say, the best camera is the one you have with you. For the past decade, a lot of my best stuff was taken on my iPhones.

Anyway. Here’s a miracle I recently discovered on how to make your low-resolution photos effectively high-res if you wanna print or publish them.

Beg, buy, or borrow Adobe Lightroom (desktop, not mobile) and then:

Open image in Lightroom.

From top menu: Photo > Enhance…

Select Super Resolution >Enhance.

Boom. Enjoy.

Be the Camera: Adventure in Passive Street Photography

Building a wearable automatic Raspberry Pi time-lapse camera that I could pin to my shirt.

Since I heard the classic Simon & Garfunkel lyric when I was little, I have dreamed of my bowtie being a camera. And today, that dream came true.

I’ve written a few articles on here about street photography… primarily the social and interpersonal, and even spiritual, aspects of it. The process, the meditative nature, the risk of offense, and the opportunity for connection. I think about this a lot. But… what if you removed all of that?

Laughing on the bus

Playing games with the faces

She said the man in the gabardine suit was a spy

I said “Be careful his bowtie is really a camera”

— Simon & Garfunkel, “America”

I’ve been taking photos since I was 6, with… a vintage 1950s Polaroid found in a closet, ‘80s Polaroid, DISC camera, countless point-and-shoots, Canon AE-1 SLR, Canon and Fuji D-SLRs, clamshell phones and every iPhone — and until today what they all had in common was that I had to think about and push a button of some kind to take a photo.

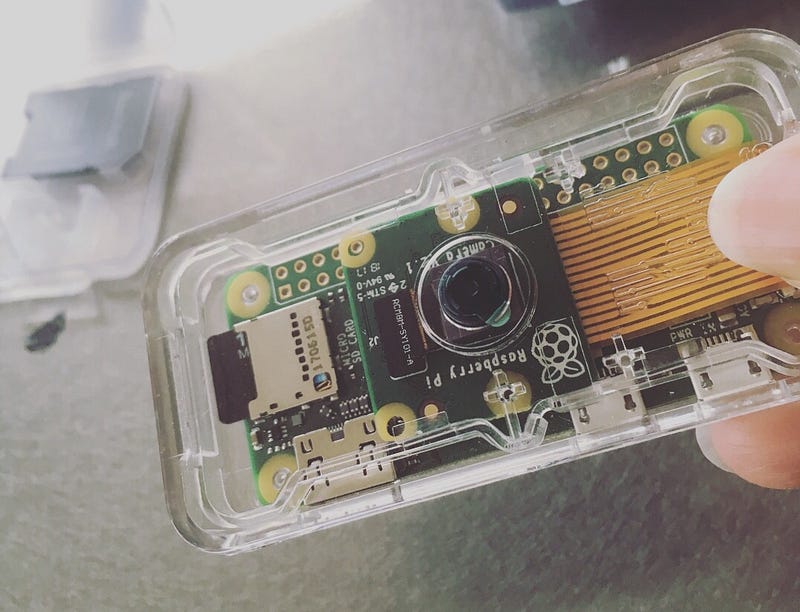

Until this weekend, when I made a wearable automatic time-lapse camera that I could pin to my shirt. It’s tiny. Really tiny.

And… I just went for a walk. I programmed it to take a photo every 60 seconds:

As you can see, nothing epic out of the box, and I’ve gotta tweak the focus and other settings. But there’s potential.

First capture. Gotta fix the focus!

Interesting experience. Being such an active photographer in general, it was oddly and almost unbearably passive. Definitely felt the loss of control. I found myself lingering in front of interesting scenes to make it likelier to get a shot. Turning my whole body to face things intentionally. Overall sensation was that I was the camera… that my body was the camera body with a lens attached.

Later, reviewing the captures, I did not have the usual sense of looking through familiar things I’d made. I had a sense of witnessing, of watching a playback of my memories. Or opening a box of surprises.

Next time I’ll set the timer for 30 seconds or less, and hit a more populated area, like a street party or downtown during rush hour. Or maybe dinner with a friend to capture a portrait of their laughs and gestures. Or run fast down the street.

Want to make one? You can do it. I’m not a programmer. This was my first time building a Raspberry Pi, and I did it with online instructions and about $50, incl. a whole starter kit. Here’s what I used: monitor (HDMI port), USB keyboard, USB mouse , 5 Things You Can Do with a Raspberry Pi Camera Module, Raspberry Pi Zero W starter kit (incl. camera case), Raspberry Pi Camera module. There’s also a low-light/infrared camera for night use.

What’s the Story? 5 Ways to Make Better Street Photos

Here are some quick tips to take your street shooting and editing to the next level. / Reprinted in PetaPixel.

Street photography is an addictive calling — the more you do it, the more you want to do it — you crave more people, more places, more action. And it’s one of the most dynamic and exciting types of photography to share on social media, with an active community around the world. Here are some quick tips to take your street shooting and editing to the next level.

Taking the shot

1. Get to know your light.

Where is east and where is west where you live? What time of day is it? Pay close attention to where tall buildings casting shadows are and where there are streetlamps or neon signs at night. Which way are your subjects walking? A subject walking toward the light makes the difference between a striking portrait and a lackluster scene. When you find a great location, think about what time of day would be absolutely perfect for your bright or “noir” shot, then return at that time of day. Become obsessive about this. Learn your city and your landscape.

Making the shot

Here are some ways to power up your photo editing — that help to hone your instincts to get a better shot in the first place.

2. Find the story and hold yourself to it.

Is it about color? Is it about angles and lines? Is it about the expression on a single person’s face? Is it a personal portrait, or is it the story of a whole street scene? Is it about how small humans are next to tall buildings, or how wide and vast the scene? What is it about? Tell yourself out loud: This is about… the look on the dog’s face, the way she’s holding that lipstick, how big Manhattan is, how empty the beach is, how fast the child is running, how many crazy colors and people there are at the carnival. Before you tap the first tool on your editing app, decide what the strength or story of your photo is, then keep it in mind as you edit and make that shine.

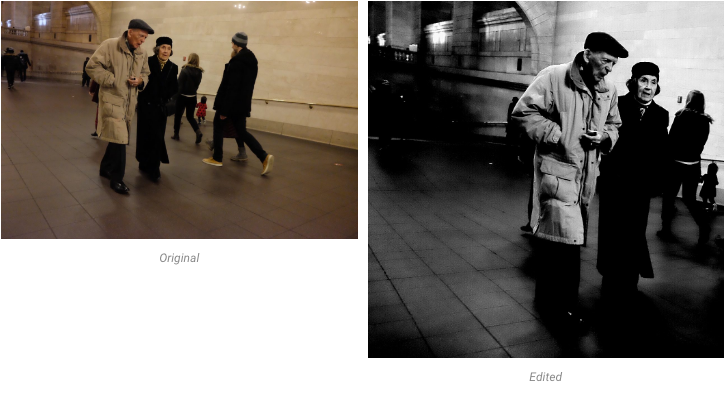

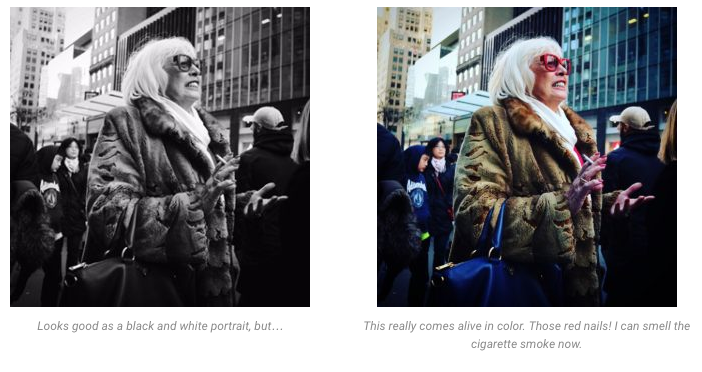

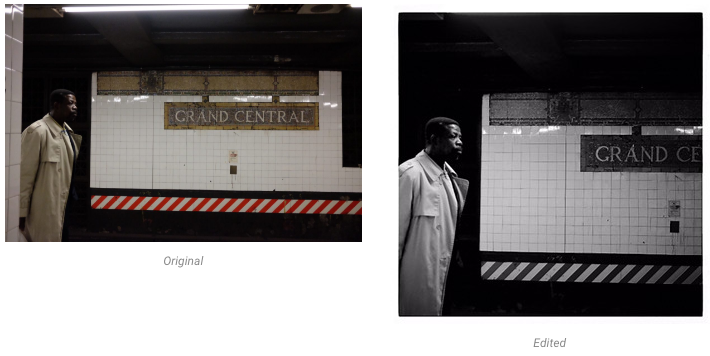

3. Color or black and white? Be intentional.

If you’ve decided that the story is about lines and shadows, or a facial expression or movement, then black & white may help you isolate that aspect. Think about how much noise you want or don’t want. Color can distract from the story you want to tell, or it can *be* the story — how green the grass is, how electric the night is, how loud the concert is, how vibrant the first day of summer in the city is. You may always publish in one or the other, but even so — make sure they are playing to their strengths.

4. Color photo? Edit in black and white first.

This is a bit like the advice to writers to either write sober and edit drunk, or vice-versa. It’s about using the lenses of different states to see things in a new way. View your color shot in black and white before you crop it — you will immediately see noisy elements that distract from your story. Cropping is the main thing here, but you may also play with shadow and vignetting etc to get a true feel for what the strongest possible version of your photo is. Trust me that this will lead to better final color photos.

Extra credit: Practice shooting in black and white. Make it a setting on your DSLR or shoot with the b&w filter on on your iPhone. The world will look different and your instinct for great composition will improve. I recently starting shooting directly in b&w, and I find that it takes care of most of what I would’ve edited later.

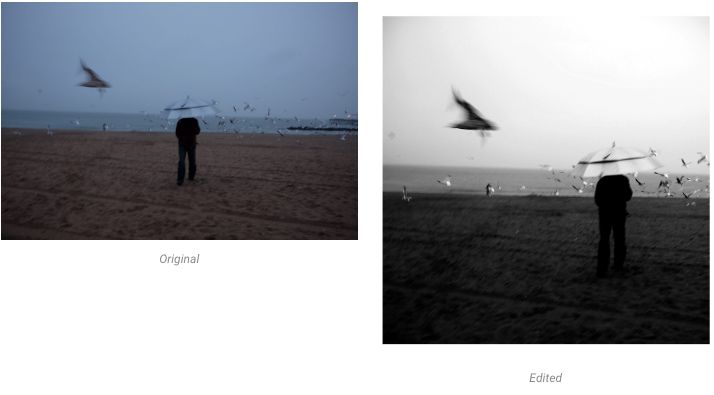

Example: There are at least two ways to crop this — horizontal or square. Viewing this in black and white, I decided the story I wanted here was the man’s expression, and went with a more intimate vignette approach rather than a letterbox contrast story.

5. Make yourself gasp.

Pretend you’ve never seen your photo before — you may have to put it away for a few hours or days to do this. Imagine you have no emotional attachment to that day or moment or how hard it was to get the shot, and that you are seeing it for the first time. Do you love it, hate it, feel anything at all? Do you have an immediate emotional response to it, or do you have to study it or think about it to “get” it? Be ruthless with yourself. Don’t make your viewer work to see the story — make it easy. Do a gut check. Surprise and delight yourself.

Example: This was a random test shot that only came alive to me in black and white. Suddenly… it transported me. It’s not my usual type of photo. I edited this while I still had the beach sand on my boots, but the final edit looks like a strange dream and continues to feel new and magic whenever I see it.

Let your stories tell themselves

Train your eye to find what is essential in your photo and to strip out anything that distracts from its power. Like a sculptor or writer, don’t be afraid to “kill your darlings” or chip away excess. Make every detail earn its place in your work, spotlight the strengths, and let your stories tell themselves.

…

Contact me or see more of my photography on Instagram and Facebook.

Tokyo Street Photography: A Brief Tour

Story of the Street street photography collective asked me to guest host their account for the week of October 1, 2016.

Story of the Street street photography collective asked me to guest host their account for the week of October 1, 2016. This series was originally published on their Instagram account. More of my Japan street photography can be found at instagram.com/jillcorral.

Day 1

Day 1

Hello and welcome to Japan! I’m @jillcorral and thrilled to bring you to Tokyo with me this week. I’ve been traveling for a few months capturing street life around the world.

In a city that pulses 24 hours a day with millions of flashing colors, why capture it in black and white? Because Tokyo truly comes alive after dark, and the light electrifies the night in tones more vivid than the sun. Street photographers often favor monochrome over color to tell stories through faces and motion, through angles and contrasts and shadows. From the blazing neon of Shinjuku to the alley lanterns of Kabukicho, there is arguably no better place for night photography than Tokyo.

Street photography is so utterly compelling because it captures both people and places, their lives and stories in fleeting moments that will never happen again. As a photographer, to me there is no greater joy than to capture a city and moment in time — to be able see and hear and feel it again in the picture. And this photo does that for me, it is my Tokyo: a bright and endless wonderland.

Day 2

Welcome back for day 2 in Japan with @jillcorral getting lost in the streets of Tokyo with open eyes and a Fujifilm X70.

Tokyo at night in the rain is a street photographer’s dream — the lights, the reflections, and of course the umbrellas. Mornings in city centers are quiet, with street cleaners, early-rising salarymen, and shuffling clubgoers who never made it home. By evening, districts like Shibuya build to a glorious frenzy that lasts well into the night.

And in the center of all that, on a rainy night there are countless stories under the umbrellas, private worlds amidst the chaos.

Day 3

Hello again and thank you for joining me @jillcorral for day 3 in Tokyo, Japan. And now we come to the crossroads of the world (or what feels like it) in iconic Shibuya. No street photography tour of Tokyo would be complete without it.

While it’s generally shown in movies as the madness and masses of rushing bodies that it truly is, what I wanted to capture here was an abstraction of it — more of an illustration than the flesh-and-blood reality. The idea of a place and the everyman in it. It also intentionally evokes the look of a Japanese graphic novel. What visual art forms can influence and energize your street photography?

This is also a terrific example of people and place coming together with perfect timing for a shot: there is a single figure dressed in black and white facing a wall of people in the distance, as well as the biggest neon billboard in the crossing being completely white and blank in that moment. I love the stillness of it — stillness with the tension and promise of imminent movement: that at any moment that wall of people will come crashing over the scene like a wave.

Day 4

Hello again, storytellers! Ready to join me @jillcorral for a quiet moment on day 4 in Tokyo?

In the teeming crowds of Tokyo, just below the tense faces of rushing workers and busy shoppers there is another world of children’s faces looking up to make sense of it all. As I mostly shoot from hip level and am rather small myself, I find that many of my most vivid photos are of expressive young people. I was thrilled to find this gentle and lovely photo on my camera on a day that I was primarily tuned into street fashion.

As street photographers, we all have different instincts for what catches our gaze and camera shutter in the blink of an eye. What drew me to these subjects was their matching hairstyles, but what stays with me is the look of curiosity in their eyes, looking with all the wonder in the world in the same direction. And the heart earring and words “good day” add to the sweetness and innocence of the mood. What catches my attention on the street in general: multiples of things (like this example), sudden movement or sounds, strong emotions or interactions, simple backgrounds, dramatic personal style, high-contrast visuals. Often what initially draws you to a scene is different than what ends up making a photo remarkable.

Day 5

Often the most interesting scenes are found when one looks away from the crowds or in an unexpected direction — the waiter smoking behind the restaurant, the faces of people watching a parade versus the parade itself. Come, take the side streets with me @jillcorral on day 5 in Tokyo.

Harajuku is the capital of Japanese youth fashion and where you see the finest displays of costumery, from anime cosplay to Victorian Lolitas to wildly original styles. On this day, I was walking behind this girl and her equally stylish friends along the packed Takeshita Street when she suddenly split off from them and headed down a side alley, where some curb diners suddenly became spectators on a runway. I love how she is all in white, part bride and part princess, and walking like royalty into the night, loyal subjects gazing after her.

Day 6

Today is our 6th and final day together in Tokyo. Feel free to ask me anything or share your own work with me @jillcorral — thanks so much for joining me this week. And now, let us gather at the top of the world.

This is taken from the rooftop of Mori Tower in Roppongi Hills, the highest outdoor observatory in Tokyo. While street photography of individual faces can be highly moving, the anonymous subject is powerful in its own way. Something I love about silhouettes is the ability to be able to see oneself in the photo. Even Tokyo itself is something of a mystery in this photo. This could be any great world city or even just the idea of a city. The two figures could be you and me, or just represent the idea of lovers and how they feel in the world. This is the story of these very real two people last Tuesday, and it is a timeless story. And while in most photos the great Tokyo looms above humans, here they stand over Tokyo like gods.

What I think makes the photo here, apart from Tokyo’s otherworldly dazzle, is the wind in the hair. Whether underground, on the sidewalk, or in the clouds, the story of the street is in these fleeting moments, small and grand, of our humanity.

On Being a Female Street Photographer

Being a women makes me vulnerable on the street, but is an advantage as a photographer. / Reprinted in PetaPixel, DIY Photography, Digital Rev.

“Being a man [street photographer] is way harder. People will think that you are a creep if you take photos of children and women.” — reader comment on my last article on public privacy

I’m 5 feet tall on a good day. People always ask me for directions and children look me in the eye. I’m low-profile and not threatening and, with my black clothes and small camera, I easily disappear into city crowds. Being a women makes me vulnerable on the street, but is an advantage as a photographer.

On the flip side, when photo subjects do notice me, some do see me as a threat to their privacy or space. Being on the receiving end of those looks is a new experience that I’ve only had in life by being on this side of a lens. Either way, it’s a delicate balance of personal safety and social awareness.

Well-known female photojournalists and street photographers, both past and present, are few and far between — Mary Ellen Mark and Vivian Maier are among the best known. List after list of top photographers online or in magazines will have maybe one or two women, if any. While this is as much the result of lack of recognition as actual numbers, we are still rare enough that I get excited to meet others, and they in turn say they’re excited to find my work.

I do think that being a woman grants a different kind of access to or received gaze from subjects. This is especially true when photographing other women, and they are most likely to be the ones I will approach if it seems like they want to engage. A common type of thing I would say is: I love your dress / style / energy /etc. You look great. I can send you the photo if you want. In general, I nod or smile or say hello to people if they notice me when out shooting.

Male subjects I am far more cautious with, from who I will take photos of to the fact that I’ll rarely walk up to them afterward (and usually only if they’re in a fixed location, e.g. sitting at a sidewalk cafe and unlikely to follow me). I don’t photograph male subjects who seem angry or aggressive or chaotic if I think there’s a chance I’ll be noticed. But, in some ways it’s easier to photograph men as they’ll often openly welcome it. (Maybe too much so in some cases, but not usually.)

This is one of my favorite photos from this year:

I love how noir it feels with the whole waterfront scene, timeless Ferris wheel, and mysterious smoking figure with a dark and brooding gaze.

Now look at the shot on my camera roll right after it, after he notices me:

It’s a warm and gentle smile, a look that I imagine a woman is likelier to receive. And I was probably smiling back. This sort of human connection is one of the things I find most compelling about shooting strangers in the wild. I see you. You see me.

Don’t be afraid, you are a woman and this is an advantage. People are more compliant with women. Go out, shoot and smile. —Elizabeth Char

So far I’ve mostly only shot in North American cities where I blend in and have native intuition about street culture and personal space. Soon I’ll be traveling around Europe and Japan, and am especially curious to see how it’ll be to hit the streets where I am visibly a foreigner and tone-deaf to local ways. Will I get more of a tourist’s “free pass” or strange looks? I find that similar rules apply both to being a solo female traveler and being a lady photog: More risk, but more and closer access to people because I am not threatening. And again, especially to other women.

Given the different personal safety and perception concerns that male and female street photographers have, I have many questions about the potential differences in their work. Do their subjects look at the lens differently — how do they respond to the photographer in front of them? Do women photographers tend to choose female subjects more than men? Less? Same? And many more. I’d love to have a larger and more diverse field of work to study and be inspired by.

Why are there not more female streettogs? Historically — and still, in many countries and cultures — women have not had the freedom to occupy public spaces in the same way as men, or to travel as freely as men, or even the means to own their own cameras.

Women are stepping up… slowly… and we are starting to take up space and reinterpret the street genre. As the numbers even out, the energy will even out. The intelligence and soul are there, and the edge is there, but it’s a powerful female energy that feels modern to me. — Sally Davies

Freedom of movement, cameras in every pocket, and global community are opening the doors wider for everyone. As far as the answers to my questions, I look forward to finding out as more and more women take on the streets of the world.

…..

This article has been reprinted on Petapixel, DIY Photography, and DigitalRev.

Don’t Take My Picture: Street Photography and Public Privacy

As an active street photographer and generally a private person myself, the question of what is a fair subject for my lens is constantly on my mind. And in the age of social media, what is fair or ethical to share to the public. / Reprinted in PetaPixel.

“Hey, don’t take our picture!” a young woman yelled out from her group to me a few days ago. I told her I didn’t take their photo — and it was true, I was just facing them playing Pokémon Go on my phone as many others were also doing in the park that day. But, often I am doing just that.

“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” — Robert Capa

As an active street photographer and generally a private person myself, the question of what is a fair subject for my lens is constantly on my mind. And in the age of social media, what is fair or ethical to share to the public.

I’m often asked about this by friends or people who see my work. On Twitter recently, a follower asked me about it, and I was glad for it as it made me put my freeform thoughts about it into words:

Then he asked: Do people ask about seeing the outcome? And I responded: Sometimes, rarely. I will always gladly delete or send it to them if requested. I also would not post if clearly an unwelcome capture.

In the United States, public space photography of pretty much anything is legal. And as far as identifiable faces, there is no need for model releases so long as a photo is not used for commercial ends (such as advertising or stock photography). But none of this is what I’m talking about here.

“I’m known for taking pictures very close, and the older I get, the closer I get.” — Bruce Gilden

Bruce Gilden.

Bruce Gilden is a well-known and controversial street photographer whose in-your-face-with-a-flash-bulb signature style produces striking results. While I find some of his work intriguing, I’ve seen videos of him shooting on the streets and share Joel Meyerowitz’s sentiment: “He’s a fucking bully. I despise the work, I despise the attitude, he’s an aggressive bully and all the pictures look alike because he only has one idea — ‘I’m gonna embarrass you, I’m going to humiliate you.’ I’m sorry, but no.”

That is one end of the spectrum, and the other is being so timid that your camera roll is full of dogs and sleeping homeless people and the backs of people walking. Between these extremes is the intersection of empathy and taking vivid and captivating pictures that tell the story of a person or a place or a moment in time.

Is it voyeuristic? Yes, in that it is about seeing. And there are as many ways to do that as there are to live. You can be creepy or curious, aggressive or gracious. Bill Cunningham, the beloved and celebrated fashion street photographer for The New York Times, devoted his life’s attention and considerable talents to capturing people being fully themselves in their natural habitats. It is clear in his decades of work and in his own words (in this great documentary) that he was there to bear witness to beauty and style. He was all about respect and admiration and celebrating his subjects, and by every evidence people enjoyed seeing him coming with a camera.

Why do I do it? So many reasons. People are fascinating. I can look at street photos endlessly — from any time or place. I spend many many hours a week traveling the world through Instagram hashtags like #everybodystreet or #lensculture or #streettog. I love the magic of fleeting everyday moments that will never happen again. I love cities and especially my city and my neighborhood and want to capture its citizens and energy, right now and forever. I love to capture all the different things that happen on that one same street corner over the years. I love the theater and chaos of an ever-changing cast of characters, how they look and how they look at each other. I love big shows of audacity and the small quiet moments in the eye of the storm. Endless fascination.

But however good my intentions or avid my interest, people have a right to their privacy wherever they are. It comes down to tuning into their cues, reading their signals, and then coming closer or moving away. Empathy, instinct, and generosity of spirit.

People have a greater or lesser sensitivity depending on the environment. In big busy cities, there is not much personal space — bodies are side by side, and there are cameras everywhere and nobody cares. It’s a different story on a quiet day on a sparsely-populated street. Or at a music festival where bodies are against and on top of each other and wanting to be seen and practically jumping in front of your lens.

Every photographer of people in the wild, whether an amateur “streettog” or a world-class photojournalist, has their own internal compass on what they will they will capture and how they will do it. The “how” is as interesting to me as the “what” and is the challenge that drives many of us to hit the streets.

In the beginning, I’d approach people and ask to take their photo, which most of the time would result in a yes and, of course, a posed photo. Not what I wanted. Street portraits are fantastic but not what I find compelling to shoot.

… the majority of photographs I take of people — people are either charmed by it, honored, or find it humbling. However it depends on how you do it. If you do it in a sneaky manner and get ‘caught’ — people are going to be pissed off. If you do it openly, honestly, and smile a lot — people won’t feel any negativity towards you. Sure you are going to get some people who look at you funny or some people who ask you to delete the photo — but that’s pretty much the worst that ever happens. — Eric Kim

As a physically small female, I am no big swaggering Bruce Gilden. My default street awareness is the same as any woman: low-level vigilance for potential threats, dialed up or down by location or time of day. And I generally fear confrontation. The anecdote I start this article with couldn’t have been a more harmless scene: sunny afternoon in well-populated park, shouted at me by a tipsy young woman sitting with a group of friends. But it still made my heart race and my cheeks flush. It is somewhat for this reason that I operate with a low profile.

Here’s how I work these days: I hold my camera in my right hand with its strap wrapped around my wrist. I shoot from hip level, rarely bringing it up to my face; partly this is my overall unobtrusive style and partly it’s the fact that my camera doesn’t have a viewfinder (just a backscreen), which I prefer. (It’s something of a modern-day Rolleiflex camera, which Vivian Maier used.)I use a fixed 28mm wide-angle lens which captures whole scenes unless I am very close. I set it to a high-speed sports mode and shoot as I walk, rarely stopping. As I walk, I get in a meditative mode, responding instinctively to sudden sounds, clamor, activity or flashes of light. I don’t overthink it. Shoot now, delete later.

If someone sees me taking their photo, I smile and nod and say hello if they are close enough to hear it. If they look like they’d rather me not be there, I’ll walk away. Sometimes I walk up to people if they look like they want to engage or would like to have the photo. Getting over the fear of directness and potential confrontation is my biggest challenge in photography, and I am evolving these skills. Openness of spirit and action is everything.

There are many beautiful photos that I’ve taken but won’t publish, because they fall outside my own guidelines. They include tender moments of love or anger or vulnerability that seem too intimate to share. Sometimes they are not-quite-illegal activity that nevertheless might not be professionally helpful. In all this, I am mindful of the emerging and widespread use facial recognition technology. The same wide-open world that makes street photography more globally accessible and immediate than ever also, not surprisingly, can make it more sensitive than ever.

I always gut check and ask myself: Why am I drawn to this person or scene? Why do I want this photo? Would I mind if someone took or publicly shared this photo of me?

For the record, I love when people take pictures of me on the street. Knowing how I myself operate, I think that I must look cool or some other vain thought, or that if I’m hideous or doing something terribly wrong then at least it’s interesting.

The problem is I’m not a good photographer. To be perfectly honest, I’m too shy. Not aggressive enough. Well, I’m not aggressive at all. I just loved to see wonderfully dressed women, and I still do. That’s all there is to it. —Bill Cunningham

Goodwill and curiosity and appreciation. Amen.

This article was republished on Petapixel. For more of my photography, please find me on Instagram, Facebook, or my gallery site.

Everything is Amazing: The Zen of Street Photography for Everybody

The Zen of street photography for everyone.

Every stock photo for “meditation” looks exactly the same: A 30-something white woman sitting in lotus position with her thumb and forefinger looped in a mudra, hands resting on her knees with her eyes closed. (Bonus points if she’s sitting on a beach or mountaintop.)

Sitting there like that does nothing for me. Apart from disappearing into the liquid oneness of a pulsing dancefloor or the waves of an ocean, there is no greater flow for me than to lose myself in a sea of urban humanity with my camera in hand.

The word Zen is derived from the Chinese word “chán” and the sanskrit word “dhyana,” which mean “meditation.” In Sanskrit, the root meaning is “to see, to observe, to look.

These days everyone has a camera in their pocket. Whether you have a thing for taking pics or not, snapping the shutter is moot: Thinking like a street photographer can open you to a new level of wonder and awareness as you move about the world.

Let go.

On the street, you control nothing.

You can be on a hot date and a dying rat will crawl across the sidewalk in front of you. (True story.) Someone can run by and knock the coffee out of your hand. Rain can start falling on your new leather jacket. Firetrucks can suddenly scream in your ear. Birds can shit on your head and then sing you a song. You can unexpectedly see your own face in the chrome of a gleaming Harley parked just so. The most beautiful boy or girl or dog in the world can pass by and look into your eyes in a way that blows your mind. Look. Listen. That thing you just saw? It will not happen again.

“Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing and when they have vanished there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.” — Henri Cartier-Bresson

Be curious about the unexpected moment and plans that go awry. When you miss the bus and have to take the next one, look at the people across from you that you may never otherwise have seen in your entire life. Click click click in your mind. Street photography is all about embracing surprises, the unusual, and seeing magic in what you least expected.

Stop. Breathe. Look around.

Do you ever get somewhere and not remember traveling there? When you are walking or going about, listen to the cars or murmurs or shouts around you, feel your feet landing on the ground, and continually bring yourself back into the moment. I always think of the common meditation instruction to “return to the breath” when the mind wanders off. In my case, when I start to obsess or stress about getting perfect shots or should I turn left or right or should I stop by the store after this or god that thing that happened at work sucked or I wish that the sun was shining the other way or that that person would just move over a little bit… if-only and what-if and should-I and and and….

Stop. Breathe. Put one foot in front of the other. Breathe. Step. Breathe. Step. Look around. Turn around.

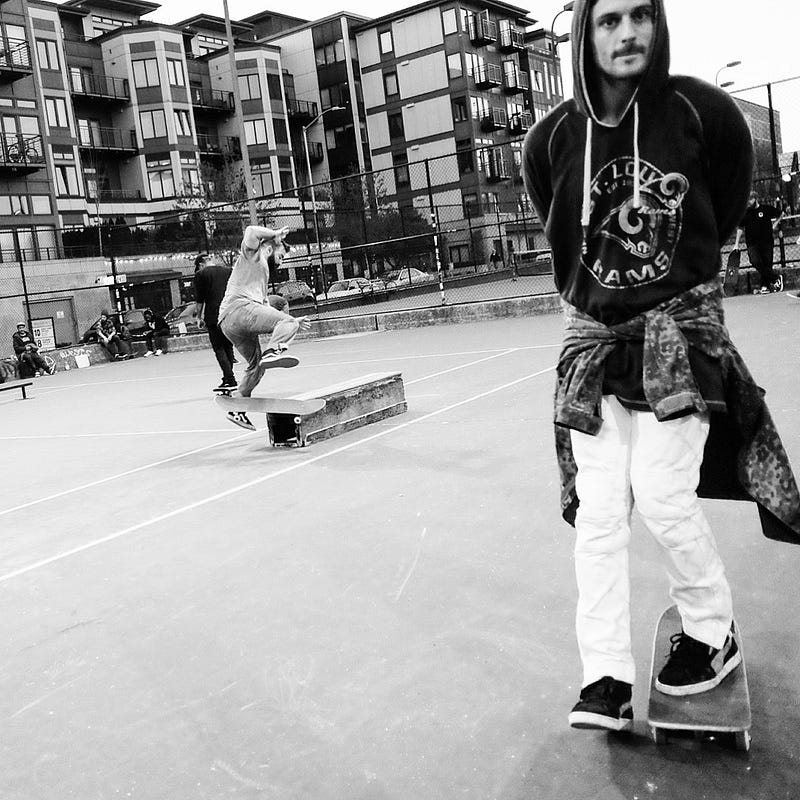

Earlier this year, I was at a local park taking shots of skateboarders on a jumps course. I was fully primed for speed, chaos, aggression and acrobatics, and I was not disappointed:

But then I stopped and mentally zoomed out on the scene. It was early on a warm Friday night and the people of Seattle were out doing things and watching other people do things.

Still standing in the same spot, I looked next to me and saw this:

This is now one of my favorite photos and the inspiration for the title of this article. Observing does not take you out of the moment or make you merely a witness. It is this state of receptiveness that lets the world in and puts you truly in it.

Stop. Breathe. Look around.

Be awake.

When I intentionally go out on a shoot—that is, when I head out with my camera to lose myself in the sea of people on purpose, it puts me in a state of heightened senses and awareness. The footsteps behind me, what direction everyone seems to be going, laughing faces under a neon sign, a sudden blast of music or yelling or barking, the smell of pizza or the perfume of an elegant woman, the busker in the light and the smoker in the shadows. I go with the flow of crowds and green lights and “walk” signs, down alleys and through gardens, toward a sound or flash of action.

When I take photographs, my body inevitably enters a trancelike state. Briskly weaving my way through the avenues, every cell in my body becomes as sensitive as radar, responsive to the life of the streets… An endless, murmuring refrain. — Daidō Moriyama

Pure response and flow. That is the purest form of this walking meditation for me. Henri Cartier-Bresson spoke of “the decisive moment” — when in this receptive state to the world around you, you instinctively take a photo. The busy mind lets go and the body responds to that instinct and world around it.

Think now of anything that you are already “primed” for in your days— the stories you collect from your workday to tell your wife at night, or that your first instinct is to tweet or Facebook when you think a clever thought, or that you always notice when Miles Davis songs are playing anywhere. We train our minds and they in turn amplify that signal to us when they witness it again.

We can train ourselves to see these fleeting and once-ever moments, not just in brief flashes but as a general way of mind. Click. Look up. Turn around. Click. And like anything else, the more you practice, the more natural and automatic it will become. Look for everyday bits of magic and serendipity and you will see them.

On your daily walk or drive or subway ride, the one you do hundreds of times a year — observe with a photographer’s mind. What moments would you capture? What is different from yesterday? What was that noise or sudden glance? What is about to happen? How can you tell? What is the story unfolding in front of your eyes?

Click click click.

For more of my photography, please find me on Instagram, Facebook, or my gallery site.